“Is it warm enough for you?” Steven Gerrard asks with a wry smile, on a steaming afternoon in Los Angeles. The fierce heat and humidity brought an early end to a training session with his new team, LA Galaxy, that morning; now, after escaping a television interview and photoshoot, the former Liverpool and England captain looks strangely cool even in his black suit and makeup. He wipes the foundation from his face. “How do people wear this stuff?” he asks, looking at it streaking across a wet wipe.

After 710 games for Liverpool and 114 caps for England, Gerrard has reached a new and serene stage of his life. It does not take him long to find an empty air-conditioned suite at LA Galaxy’s stadium. He takes off his jacket and kicks off his shoes. He looks more relaxed than he has at any point over the many times I’ve interviewed him this year.

In the course of writing his autobiography together, we’ve met in all kinds of places: a genteel golf club in Formby, a hotel room in Crewe, Liverpool’s training ground and Raheem Sterling’s old house (which Gerrard rented while his family prepared to move to California). This is very different. A vast blue American sky stretches out in front of us, the huge windows shimmering in the sunlight. We’re a long way from the Bluebell estate, where Gerrard grew up in Liverpool, and a long way from Anfield.

Looking down at the StubHub Center, where he now plays, Gerrard explains the contrast between English football and American soccer, between Huyton and Hollywood. “It’s more relaxed here,” he says. “The intensity is less. People come for a day out with the family – it’s more of a festival atmosphere. The Premier League is aggressive. In England, you feel the pressure rolling down from the terraces. You feel like you have to impress the manager every day, to impress tons of people every time you perform. After 17 years in that pressure cooker, America’s a great change.”

But he still misses home. “The first time was when Liverpool were at Stoke for the first game of the [Premier League] season,” Gerrard says. “I watch every game, and I do wish I was 25 again and captain, and leading them out in front of our supporters. I loved playing in the Premier League and the Champions League. We’ve got the best league in the world, so you are going to miss it – especially when you’ve spent a lifetime at your home town club.”

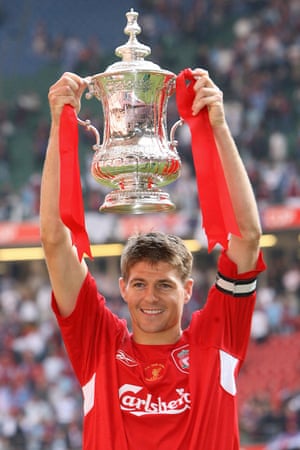

In an era when footballers are often reviled for their readiness to swap one club for another, kissing a new badge while grabbing their latest multimillion-pound contract, Gerrard defined loyalty. He played for Liverpool from the age of eight to just a few days before he turned 35. As a skinny little kid he kicked a ball around on the Bluebell estate and pretended to be his Liverpool heroes: John Barnes,Steve McMahon, John Aldridge and Peter Beardsley. At his best, he fused whole-hearted passion with brilliant technique – a driving and goalscoring midfielder who delivered trademark 35-yard cross-field passes with weighted precision. In 2005, Gerrard inspired Liverpool to become champions of Europe. He remains the only player in footballing history to have scored a goal in the finals of the Champions League, the Uefa Cup, the FA Cup and the League Cup.

But not even Gerrard could keep playing for ever in the red of Liverpool. As a footballer, it tore a chunk out of him to leave – but the human benefits are obvious. “A lot of people have noticed how different I am in LA,” Gerrard tells me. “Alex [his wife], my family and friends see a huge difference. It’s the first time Alex has seen me without that pressure I’ve lived with for so long – and the first time the kids [their daughters Lilly-Ella, Lexie and Lourdes] have seen me so free and easy. They’ve been surprised that, whatever they have asked me to do in LA, I’m like, ‘Yeah, come on, let’s do it.’ At home, if they want to go to the swimming baths or a fairground, it’s tough. You have to be selective about where you go, because there is so much attention on me.” He grins in relief. “Here, it’s the opposite. I’m a Z-lister. It’s perfect for me. I feel so much lighter.”

On one of their first nights in LA, in late June, he took Alex out for dinner at Nobu in Malibu. “Kim Kardashian and Kanye West were at the next table,” he says drily. “You should’ve seen Alex. She was carrying on like I would carry on if it wasMaradona or Pelé sat next to us. Alex was gawping at them for the majority of the meal, but I’m different. I’m a big fan of Kanye West’s music, but I don’t get carried away when I see anyone famous. I’ve seen quite a few knocking about and I know it’s important to leave them alone.” He didn’t lean over and say hello? “No. Being in the position I’m in at home, I know how important it is to give people privacy.”

Gerrard really does relish being a Z-lister. Back in Liverpool, we met only once in the city centre. It was too difficult for him to travel into town: the red half of Liverpool smothers him with an adoration that can sometimes be as edgy as it is deep; the blue half, belonging to Everton, has given Gerrard “proper abuse” over the years. The mania of English football meant he could never take his daughters for a swim or pick them up after their dance class, never do the dad stuff.

Cynics will point to a recent issue of Hello! magazine in which the Gerrards and their new (rented) home – an “$18m [£11.7m], six-bedroom, eight-bathroom house, where Mariah Carey once lived and where the neighbours include Simon Cowell” – are featured in a lavish 12-page spread. “That’s down to Alex.” He shrugs. “She likes to do modelling shoots, and I like to support her. But you’ll see I’m in about two of the pictures. I always come in for the last hour. It’s Alex’s hobby and she enjoys it. She’s a great support to me as a wife, so when she asks for a little support on one of her shoots, it’s the least I can do. But do I like being splashed all over Hello! magazine? Not really.”

Alex is not the archetypal footballer’s wife. When I met her at their home in Formby, she walked shyly into the kitchen, laden down with groceries, as down-to-earth as her husband. Gerrard describes her as “the shyest person I have ever met” – even if she doesn’t mind having her photograph taken.

Gerrard had his family with him at his final home game in May this year (a 3-1 defeat to Crystal Palace). After the match, he gazed longingly up at the stands as his daughters walked next to him across the pitch, in matching apricot-and-cream outfits, their father looking proud, sad and happy all at the same time. Anfield could not be contained. The same song echoed over and over as he raised his hand in farewell:

Stevie Gerrard is our captain

Stevie Gerrard is a red

Stevie Gerrard plays for Liverpool

A Scouser born and bred

Stevie Gerrard is a red

Stevie Gerrard plays for Liverpool

A Scouser born and bred

***

José Mourinho made many attempts to sign Gerrard for Chelsea, the most notorious of which was in 2005, when Liverpool had just won the Champions League. Gerrard was tempted but, as he remembers, “My dad asked me a simple question: ‘Would it mean more to you to win two or three trophies with Liverpool than double that number with Chelsea?’ I wasn’t thinking about Chelsea then. I was thinking only of Liverpool. Dad understood. He said, ‘Don’t walk away. Don’t leave the club that you love.’ And I never regretted staying at Liverpool my whole career in England.”

Had Gerrard moved to Chelsea in the summer of 2005, he could have won 10 trophies; as Liverpool captain, he lifted two in the same period. He would also have made much more money. But his loyalty is instinctive, as are the values that mean he has always refused an image rights deal (where a player makes money every time his club features his face in a commercial). “You hear other players talking about image rights and how much it earns them. Personally, I think it’s disgusting for a player to ask for image rights from his club. I believe that when you sign a contract, you sign your image rights over to them. They pay you well, and you’re working for them. Maybe it’s different if you’re Messi or Ronaldo.

“But there’s so much money in football now, because of the television deals, and it seems to be getting worse,” Gerrard says. “I think we’ll see players moving an awful lot more, because agents will always push for the next move. My own focus has always been football. It’s something my mum and dad handed down to me – the idea that you should just be the best you can be and everything else will take care of itself. You avoid becoming greedy. You concentrate on becoming a good footballer, rather than a personality or a brand.”

Yet, as Gerrard admits, the fact that he is driven by emotion meant he was sent off eight times in his 17-year career as a Liverpool player, half of them against two clubs, Manchester United and Everton. “Against the teams we always wanted to beat most, I played closest to the red zone,” he says.

Gerrard was at his most emotionally vulnerable during the final months of his Liverpool career, when he had to put up with my incessant questions. What was his darkest moment? Is he happy? What was going on inside his head when he stamped on Ander Herrera and got sent off after 38 seconds against Manchester United in March this year? What kind of dad is he? What impact has Hillsboroughhad on his family? (Gerrard’s 10-year-old cousin, Jon-Paul Gilhooley, was the youngest of the 96 Liverpool fans who lost their lives in 1989.) How does it feel to have 40,000 people taunting him in a song? Does it still hurt that he never won the Premier League? Has he ever needed to see a psychiatrist? Can we do this all again for a few hours tomorrow?

Instead of throttling me, Gerrard answered every one. It helped that he has an apparent preference for talking about the dark and low moments, skirting quickly across glory and victory. In this, he’s very different from most footballers I’ve met – more reflective, questioning, and brutally honest.

***

At every game Gerrard played last season, opposition fans roared the same old songs:

Or, when they got bored, swapping it for another chestnut:

You nearly won the league

You nearly won the league

And now you better believe it

Now you better believe it

You nearly won the league

You nearly won the league

And now you better believe it

Now you better believe it

You nearly won the league

On 27 April 2014, Liverpool lost 2-0 to Chelsea, a defeat that cost them the Premier League title. Gerrard slipped, Chelsea’s Demba Ba raced away and scored, and in that moment Liverpool’s unstoppable surge faltered. “It was the toughest moment of my career by a mile,” Gerrard says. “At the end of the game, I just wanted to be under the ground. When we left Anfield, I was in the back of the car. We were on the way home and the tears were rolling down my face. It was killing me.

“I was with Alex and Gratty [Paul McGrattan], one of my best mates, but I was numb. I had that feeling you get when you’ve lost a family member, that’s how bad it felt. The tears kept coming. I was 33 years old and I hadn’t cried for years. Alex and Gratty were saying, ‘Look, it can still change, there’s still a few games to go…’ But I knew.”

Liverpool’s supporters had sung You’ll Never Walk Alone but, in the car, Gerrard felt “very alone. I didn’t feel like I had much hope then. It seemed like I was heading for suicide watch.”

Gerrard can be amusing company but, essentially, he is a serious man. He is not being sensationalist when he says he felt as if he was on “suicide watch”, but he clarifies: “I wasn’t suicidal. I’ve never been suicidal. I can just imagine that people who are suicidal might feel pretty similar to how I did. For the next 24 to 48 hours, I needed Alex next to me. Because of the type of person I am, the worst thing I could have done was to be alone. I had to get away with Alex and I remembered being in Monaco once and it was like a ghost town. So we ended up there for a few days.”

On the phone from Monaco, Gerrard spoke to Steve Peters, a sports psychiatristwho has helped him in the past, as well as Olympic champions such as Chris Hoyand Victoria Pendleton. Peters reminded Gerrard that he had experienced the glory of victory as well as defeat. That simple message resonated.

Gerrard had first turned to Peters in 2011, when, injured, he was convinced his career was over. Footballers are not usually comfortable discussing psychological frailty, but Gerrard is bluntly candid. “Steve asked me some tough questions in 2011. He said, ‘If you never kick a ball again, so what? You’ve got three beautiful, happy little girls. You’re married to a lovely wife who supports you every step of the way. You’re a lucky man. You’ve had an unbelievable career. You’ve won the biggest trophy in club football. You’ve played so many times for your country. You live in a very nice house. You’re financially secure for the rest of your life. What are you worried about?’

“I was sick with worry that my career might be over. But Steve knew young sportsmen and women who had been forced to retire after six months, before they’d had a chance to achieve anything. They had no medals to show for their commitment. They had no money. How lucky was I compared with them? Steve reminded me that people were in trouble in all walks of life. Some men gambled everything and ruined their lives. Others drank their lives away. Of course he was right.”

Gerrard got things into perspective. “I’m not big-headed,” he once told me. “I’m the other way. I’m probably too harsh on myself. But I’m also clever enough to analyse it and come out with the right answers. And the simple fact is I’ve achieved things that I didn’t dream I’d ever get near. I’ve played in World Cups and Champions League finals. I’ve scored goals and won games that would have shocked me as a kid. I’ve given absolutely everything to Liverpool in training, in the games, off the pitch. I can’t do any more. But it’s still tough, to this day.”

Typically, Gerrard was readier to talk about the harsh disappointment of The Slip than the greatest moment of his career – the Miracle of Istanbul, when he led Liverpool’s remarkable comeback against Milan in the 2005 Champions League final. Liverpool were 3-0 down at half-time when Gerrard scored their first goal (followed immediately by Vladimír Šmicer’s second); just five minutes later, he earned the penalty that led to the incredible equaliser. Liverpool won the game on penalties and, at 25, Gerrard lifted the trophy that matters most in club football.

“There have been DVDs, books and films about it,” Gerrard said when I first asked him about it. “Ten years of milking it is enough.” He was relieved to miss the 10th anniversary celebrations, because he was away. “I think the next time you’ll see me at an Istanbul event will probably be in 40 years, when it’s the 50th anniversary. I’ll be nice and old then – 75.”

But he eventually relented, capturing all the drama and intensity of an unforgettable night. “We went as crazy as you would expect. We yelled and danced and ran around like idiots. I look back now in amazement. Was that really me? I celebrated like I deserved to celebrate. Correct me if I’m wrong, but have you ever seen a better Champions League final? Every single one of Milan’s players was either world class or very close to it. They were a better team than us, but we beat them.

“It was not just luck. The big moments in the second half went our way but, after we got back to the dressing room, I saw how much we had given. There were cuts everywhere, bruises, ice, bandages, sweat, dirt and plenty of tears. It looked like we had been to war.”

All these years later, on an afternoon hazy with heat, it is hard to imagine such intensity. Life feels peaceful in LA. Having stepped away from “the pressure cooker”, Gerrard feels a calm pride. “My dad’s a quiet man,” he explains, “but he talked quite a bit to me in my last week as a Liverpool player. He said, ‘What a career. What loyalty. Look at your figures, your games and trophies, and look at your send-off. Look at your people, look at your legacy. Imagine how it would have felt if you’d have finished your career at another club. You would never have got such respect. You did great.’”

Gerrard smiles; even if he still yearns for Liverpool, England and European football, there’s one thing he’s happy to have escaped. “I haven’t missed hearing that old Slip song – but I’m coming back to BT as a pundit as often as I can. I know they’ll put that record on again.”

Since Gerrard began playing for LA Galaxy in early July, the team have risen up the Western Conference in Major League Soccer, a competition split into two geographical divisions. They are now just a point behind the leaders, theVancouver Whitecaps, and almost certain to be in the play-offs at the end of October. The MLS doesn’t carry the prestige or gravitas of championships in Europe and England, but it matters hugely to Gerrard.

“I’ve come here to win and finish my career on a high,” he says. “The MLS is a fantastic league and it’s growing all the time. The lads here are really professional and fit. The away games are different. You’re either faced with long travel, humidity, heat or altitude. It’s nice to be in Beverly Hills and LA, but if you watch me play, you’ll see I want to win as much as ever. That’s not going to change. It’s in my DNA.”

He might play on when his 18-month contract expires – or go home to England and prepare for a new career. The dream scenario is an eventual return to Liverpool as a coach or manager, but Gerrard is too smart to make any predictions. For now, “It’s great that you wake up in the morning and the sun’s shining and you’re driving into work, and you know you’ve got a hard training session ahead. I like that, because I’ve got the same competitive instinct.”

Philosophy and sunshine don’t always go together but, gazing at the blue California sky, Gerrard sounds as reflective as he is accepting. Life as a 35-year-old man, and footballer, is richer and better than he ever expected. “All the highs and lows are so clear. I remember them like they happened yesterday. They made me who I am. And, right now, life feels pretty good.”

Source:TheGuardian

EmoticonEmoticon